Yeast makes beer; brewers make wort. Once this sugary substrate is sealed up inside our fermentation tanks, our brew day is done and we can wait for our microscopic friends to finish the job. So how do we get from bins full of crushed grains to sweet, delicious yeast food?

Our tiny hot side is centered around three big brew vessels – a hot liquor tank, a mash tun, and a boil kettle. Those brew vessels are at the heart of every beer we make, and we spend most of any given brew day tending to them, heating and cooling and moving grains and hops and water around on the way to the finished wort.

The hot liquor tank, or HLT, is basically just a staging ground, a 200L pot to hold each specially-formulated batch of water before we combine it with the grist. That said, a lot of thought and work has gone into its construction. Two beefy 5.5kW elements provide the heating, controlled by a beautiful custom panel from Grounded Brewtech which allows us to see and command every aspect of the hot side at a glance.

The HLT is also home to our Heat Exchange Recirculating Mash System, or ‘HERMS’. Despite the daunting acronym, this is really just a large steel coil embedded in the HLT, a sealed loop through which we recirculate our brewing liquor during the mash. The HERMS allows us to hold our brew at a constant temperature without worrying about heat loss, and to raise or lower that temperature as we need.

The mash tun is the next step in the brew day. While our grains are milling, we move our ‘strike’ water from the HLT into the mash tun and begin recirculating it through the HERMS coil to stabilise its temperature. We then add our grains to the strike water, carefully mixing to break up any dough balls. A large perforated filter sits at the bottom of the mash tun, straining out the solid grain husks and grit, and allowing the recirculating water to gently wash the grain.

Anyone familiar with our beers knows that we like playing with high-alcohol and big-body styles (try our “Singularity” Irish Coffee Stout for a delicious example of both!) and for these we need to compromise a bit. Ideally, we’d like a lot of water per kilo of grain, to help the sugars dissolve more readily and improve our extraction rate, but our mash tun only holds 160L in total. So on our bigger brews, more grain means less water, a thicker mash, with lower extraction efficiency and a lot more manual stirring to avoid clogging the mash filter.

After 60 minutes of mashing, the starches in our grain have all been converted, into either fermentable sugars or body-building dextrins which will persist into the finished beer. It’s time to move the wort into our boil kettle for the hops additions, but we want to pull as much sugar and flavour from the mash as we can. So as we slowly drain our wort into the kettle, we gently spray hot water over the top of the mash bed; this final rinse is called the ‘sparge’ and loosens up the remaining sugars to pull them into the boil kettle.

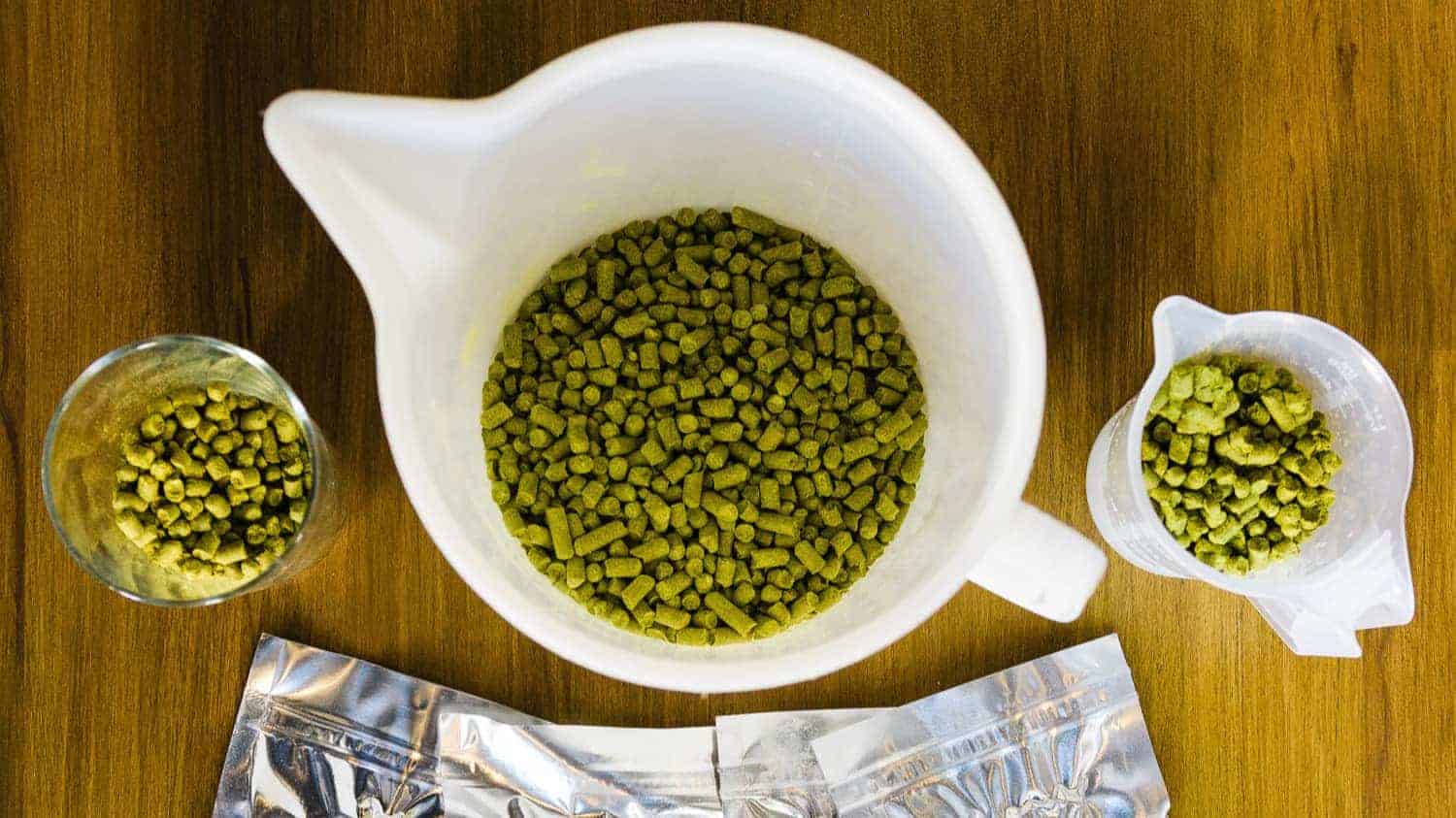

All told, our 25-50kg of grains will end up as roughly 150L of pre-boil wort, and if we’re lucky we’ll get 75-80% of their sugar content into our kettle. From there, it’s time for everyone’s star ingredient: hops! See you in two weeks!